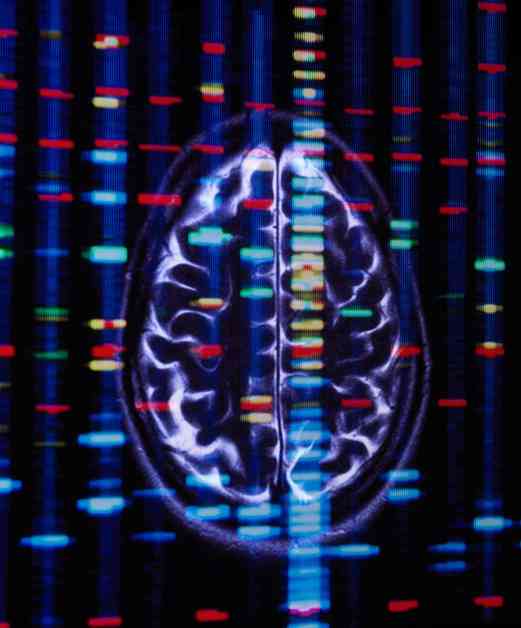

New evidence suggests that the effects of trauma (war, genocide, abuse, environmental factors, etc.) could be passed down genetically from one generation to the next. Epigenetics is the study of how genes are activated and inhibited. This molecular process, known as «gene expression,» stimulates the activity of certain genes and silences others by adding and removing chemical markers (methyl groups) on the genes. Multiple studies have already suggested that this could be a mechanism by which a parent’s trauma could be imprinted in the genes of their offspring; epigenetic effects could also be multigenerational.

For some people, the idea that we could carry the legacy of trauma makes sense, as it validates the feeling that they are more than the sum of their experiences. «If you feel like you have been affected by a very traumatic, difficult, upsetting event that your mother or father experienced, well, there’s a reason for that,» explains Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and trauma neuroscience at Mount Sinai in New York. According to her research, attention is drawn to a small epigenetic «signal» that shows that a traumatic experience «does not disappear when you die.» «It survives in a certain form.»

To understand how emotional trauma can transcend generations, it is good to think about the distinction between the genome (the total DNA present in the body) and the epigenome. Isabelle Mansuy, a professor of neuroepigenetics at the University of Zurich, compares this to the difference between software and hardware, between computer software and hardware. You need the «hardware» of the genome to function. But it is the epigenetic «software» that tells the genes of the genome how to function.

In a 2019 study of male Australian Vietnam War veterans, researchers tracked differences in DNA methylation in the sperm of veterans with PTSD and compared it to the DNA of those without the disorder. Ten regions of DNA from veterans with PTSD showed different methylation patterns compared to those without PTSD. Changes were present on nine different genes associated with psychiatric disorders such as PTSD.

Despite the concerns raised by these studies, preliminary evidence suggests that some epigenetic changes can be reversed. Isabelle Mansuy and her colleagues hypothesized that an enriched environment could mitigate trauma-related behaviors. In several experiments, she placed traumatized adult mice in cages with wheels, toys, and mazes with other mice. Compared to traumatized mice in normal cages, traumatized mice in a more stimulating environment showed no signs of traumatic behavior. And neither did their offspring.

Michael Skinner has studied seventy pairs of identical human twins who agreed to have their exercise levels monitored. In more physically active twins, rates of obesity and metabolic diseases were lower. And their epigenome changed as well. Twins who exercised more had chemical markers on their genes associated with a lower incidence of metabolic syndromes.

While it is easy to focus on the negative aspects of potentially inheriting the effects of trauma, epigenetic changes can also help future generations by activating genes that will allow them to cope with adversity. «This is what I think is happening,» says Rachel Yehuda. But it depends. If you do not live in adversity, you may become hyper-vigilant. And if you live in adversity, you may have skills to face it honed by the life lessons of the past in one way or another.

In conclusion, while the mechanisms of inheriting trauma effects are still being researched and debated, it is clear that humanity has learned to manage the effects of trauma, whether inherited or not. Resilience is a dominant trait that has enabled us to survive and thrive as a race. As we continue to explore the complexities of epigenetics and trauma inheritance, further research and understanding will shed light on the intricate ways in which our experiences shape our genetic inheritance.